![]()

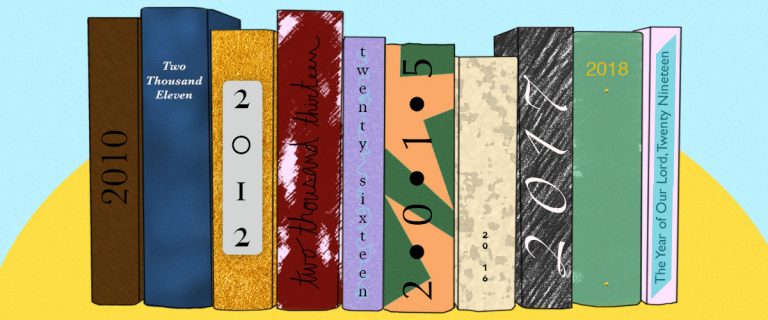

Friends, it’s true: the end of the decade approaches. It’s been a difficult, anxiety-provoking, morally compromised decade, but at least it’s been populated by some damn fine literature. We’ll take our silver linings where we can.

So, as is our hallowed duty as a literary and culture website—though with full awareness of the potentially fruitless and endlessly contestable nature of the task—in the coming weeks, we’ll be taking a look at the best and most important (these being not always the same) books of the decade that was. We will do this, of course, by means of a variety of lists. We began with the best debut novels, the best short story collections, the best poetry collections, the best memoirs of the decade, and the best essay collections of the decade. But our sixth list was a little harder—we were looking at what we (perhaps foolishly) deemed “general” nonfiction: all the nonfiction excepting memoirs and essays (these being covered in their own lists) published in English between 2010 and 2019.

Reader, we cheated. We picked a top 20. It only made sense, with such a large field. And 20 isn’t even enough, really. But so it goes, in the world of lists.

The following books were finally chosen after much debate (and multiple meetings) by the Literary Hub staff. Tears were spilled, feelings were hurt, books were re-read. And as you’ll shortly see, we had a hard time choosing just ten—so we’ve also included a list of dissenting opinions, and an even longer list of also-rans. As ever, free to add any of your own favorites that we’ve missed in the comments below.

***

The Top Twenty

![]() Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow (2010)

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow (2010)

I read Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow when it first came out, and I remember its colossal impact so clearly—not just on the academic world (it is, technically, an academic book, and Alexander is an academic) but everywhere. It was published during the Obama Administration, an interval which many (white people) thought signaled a new dawn of race relations in America—of a kind of fantastic post-racialism. Though it’s hard to look back on this particular zeitgeist now (when, and I still can’t believe I’m writing this, Donald Trump is president of the United States) without decrying the ignorance and naiveté of this mindset, Alexander’s book called out this the insistence on a phenomenon of “colorblindness” in 2012, as a veneer, as a sham, or as, simply, another form of ignorance. “We have not ended racial caste in America,” she declares, “we have merely redesigned it.” Alexander’s meticulous research concerns the mass incarceration of black men principally through the War on Drugs, Alexander explains how the United States government itself (the justice system) carries out a significant racist pattern of injustice—which not only literally subordinates black men by jailing them, but also then removes them of their rights and turns them into second class citizens after the fact. Former convicts, she learns through working with the ACLU, will face discrimination (discrimination that is supported and justified by society) which includes restrictions from voting rights, juries, food stamps, public housing, student loans—and job opportunities. “Unlike in Jim Crow days, there were no ‘Whites Only’ signs.” Alexander explains. “This system is out of sight, out of mind.” Her book, which exposes this subtler but still horrible new mode of social control, is an essential, groundbreaking achievement which does more than call out the hypocrisy of our infrastructure, but provide it with obvious steps to change. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

![Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Emperor of All Maladies]() Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Emperor of All Maladies (2010)

Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Emperor of All Maladies (2010)

In this riveting (despite its near 600 pages) and highly influential book, Mukherjee traces the known history of our most feared ailment, from its earliest appearances over five thousand years ago to the wars still being waged by contemporary doctors, and all the confusion, success stories, and failures in between—hence the subtitle “a biography of cancer,” though of course it is also a biography of humanity and of human ingenuity (and lack thereof).

Mukherjee began to write the book after a striking interaction with a patient who had stomach cancer, he told The New York Times. “She said, ‘I’m willing to go on fighting, but I need to know what it is that I’m battling.’ It was an embarrassing moment. I couldn’t answer her, and I couldn’t point her to a book that would. Answering her question—that was the urgency that drove me, really. The book was written because it wasn’t there.”

His work was certainly appreciated. The Emperor of All Maladies won the 2011 Pulitzer in General Nonfiction (the jury called it “An elegant inquiry, at once clinical and personal, into the long history of an insidious disease that, despite treatment breakthroughs, still bedevils medical science.”), the Guardian first book award, and the inaugural PEN/E. O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award; it was a New York Times bestseller. But most importantly, it was the first book many laypeople (read: not scientists, doctors, or those whose lives had already been acutely affected by cancer) had read about the most dreaded of all diseases, and though the science marches on, it is still widely read and referenced today. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

![Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (2010)]() Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (2010)

Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (2010)

As a strongly humanities-focused person, it’s difficult for me to connect with books about science. What can I say besides that public education and I failed each other. When I read The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, I found myself thinking that if all scientific knowledge were part of this kind of incredibly compelling and human narrative, I would probably be a doctor by now. (I mean, it’s possible.) Rebecca Skloot tells the story of Henrietta Lacks, a black woman who died of cervical cancer in 1951, and her cells (dubbed HeLa cells) which were cultured without her permission, and which were the first human cells to reproduce in a lab—making them immensely valuable to scientists in research labs all over the world. HeLa cells have been used for the development of vaccines and treatments as well as in drug treatments, gene mapping, and many, many other scientific pursuits. They were even sent to space so scientists could study the effects of zero gravity on human cells.

Skloot set a wildly ambitious project for herself with this book. Not only does she write about the (immortal) life of the cells as well as the lives of Lacks and her (human, not just cellular) descendants, she also writes about the racism in the medical field and medical ethics as a whole. That the book feels cohesive as well as compelling is a great testament to Skloot’s skills as a writer. “Immortal Life reads like a novel,” writes Eric Roston in his Washington Post review. “The prose is unadorned, crisp and transparent.” For a book that encompasses so much, it never feels baggy. Nearly ten years later, it remains an urgent text, and one that is taught in high schools, universities, and medical schools across the country. It is both an incredible achievement and, simply, a really good read. –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

![Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands]() Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands (2010)

Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands (2010)

Timothy Snyder’s brilliant Bloodlands has changed World War II scholarship more, perhaps, than any work since Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, an apt comparison given that Bloodlands includes within it a response to Arendt’s theory of the banality of evil (Snyder doesn’t buy it, and provides convincing proof that Eichmann was more of a run-of-the-mill hateful Nazi and less a colorless bureaucrat simply doing his job). Snyder reads in 10 languages, which is key to his ability to synthesize international scholarship and present new theories in an accessible way. But before I continue praising this book, I should probably let y’all know what it’s about—Bloodlands is a history of mass killings in the Double-Occupied Zone of Eastern Europe, where the Soviets showed up, killed everyone they wanted to, and then the Nazis showed up and killed everyone else. By focusing on mass killings, rather than genocide, Snyder is able to draw connections between totalitarian regimes and examine the mechanisms by which small nations can suddenly and horrifyingly become much smaller. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

![the warmth of other suns]() Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (2010)

Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (2010)

Wilkerson’s history of the Great Migration is a revelation. When we talk about migration in the context of American history, we tend to focus on triumphalist stories of immigrants coming to America, but what about the vast migrations that have happened internally? Between 1920 and 1970, millions of African-Americans migrated North from the prejudice-ridden South, lured by relatively high-paying jobs and relatively less racism. It takes a whole lot to make someone leave their home, and Wilkerson does an excellent job at reminding us how awful life in the South was for Black people (and still is, in many ways). The Warmth of Other Suns is not only fascinating—it’s also thrilling, taking us into the lives of hard-scrabble folk who were equal parts refugees and adventurers, and truly epic, telling a great story on a grand scale. Don’t think that means there aren’t small moments of humanity seeded throughout the book—for every sentence about the conduct of millions, there’s a detail that reminds us that we’re reading about individuals, with their own hopes, wishes, dreams, and struggles. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

![Robert A. Caro, The Passage of Power]() Robert A. Caro, The Passage of Power: The Years of Lyndon Johnson (2012)

Robert A. Caro, The Passage of Power: The Years of Lyndon Johnson (2012)

While Robert Caro first came to prominence for The Powerbroker, his 1974 biography of divisive urban planner Robert Moses, it’s Caro’s ongoing multi-volume biography of LBJ, America’s most unjustly maligned president (fight me, Kennedy-heads!), that has cemented his legacy. It’s hard to pick one in particular to recommend, but The Passage of Power, which covers the years 1958-1964, captures the most tumultuous period of LBJ’s life in politics, as he went from feared senator, to side-lined VP, to suddenly becoming the post powerful figure in the world. There’s something profoundly moving about the vastness of these works—Caro is 83 now, and has dedicated an enormous part of his life to this singular project. His wife is his only approved research assistant, and together, they’ve upended half a century of LBJ criticism to reveal the complex, problematic, but always striving core of a sensitive soul.

I had a teacher in high school who spent 20 years working on her dissertation on LBJ. She’d spend each weekend at the LBJ Library at UT Austin, while working full time as a public school teacher, and kicked ass at both. There’s something about LBJ that inspires people to dedicate their entire lives to trying to figure him out, and in the process, trying to understand the world that made him, and that he made. Thanks to Caro, we can all understand LBJ a little bit better. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

![Tom Reiss, The Black Count]() Tom Reiss, The Black Count: Glory, Revolution, Betrayal, and the Real Count of Monte Cristo (2012)

Tom Reiss, The Black Count: Glory, Revolution, Betrayal, and the Real Count of Monte Cristo (2012)

Tom Reiss opens his biography of Thomas Alexandre-Dumas, father of author Alexandre Dumas, with a scene that seems right out of an academic heist film. At a library in rural France, Reiss convinces a town official to blow open a safe whose combination was held only by the late librarian. What Reiss discovers are the rudiments of a grand and, until then, largely unknown story of the man who inspired some of his son’s most beloved tales. The Black Count is also a case study of complex racial politics during the age of revolutionary France. Dumas was born in 1762 in Saint-Domingue, the French Caribbean colony that would become Haiti. As the son of a French marquis and a freed black slave, Dumas was subject both to the privileges of the former and the kind of indignities suffered by the latter. His father, for instance, sells him into slavery when he is 12 only to purchase his freedom later and bring him to France, where the young man receives an aristocratic education. A final rift from his father prompts Dumas to join the military. Reiss creates a dynamic, if somewhat speculative portrait of Dumas based on letters, reports from battlefields, Dumas’ own writings, and more. By the time he is 30, Dumas has vaulted in the ranks from corporal to general and commands a division of more than 50,000 soldiers. It’s no accident that the thrilling militaristic feats Reiss describes sound like events out of The Count of Monte Cristo or The Three Musketeers. Though the general becomes a cavalry commander under Napoleon Bonaparte, Reiss suggests that it was Napoleon himself who ruined Dumas not only from a personal standpoint, but civilizational as well. Napoleon reintroduced slavery in Haiti, after all, in contradiction to the republican dreams of Dumas’ contemporary, Toussaint Louverture, another rare and successful 18th-century general of African descent. Reiss unearths the ultimately tragic story of a man who was infamous in his own time for enjoying social and professional advantages that would’ve been unheard of for a mixed-race man in the US, a nation which of course went through its own revolution one generation earlier. –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

![Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction]() Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction (2014)

Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction (2014)

The premise of Elizabeth Kolbert’s Pulitzer-prize-winning book is a simple scientific fact: there have been five mass extinctions in the history of the planet, and soon there will be six. The difference, Kolbert explains, is that this one is caused by humans, who have drastically altered the earth in a short time. She points out on the first page that humans (which is to say, homo sapiens, humans like us) have only been around for two hundred thousand or so years—an incredibly short amount of time to do damage enough to destroy most of earthly life. Kolbert’s book is so unique, though, because she combines research from across disciplines (scientific and social-scientific) to prepare an extremely comprehensive, sweeping argument about how our oceans, air, animal populations, bacterial ecosystems, and other natural elements are dangerously adapting to (or dying from) human impact, while also tracing the history of both the approaches to these things (theories of evolution, extinction, and other principles). It’s a depressing and horrifying argument on the face of it, but it’s made so delicately, even poetically—Kolbert’s concerned, occasional first-person narration, and her many interviews with professionals capable of the pithiest, most perfect quotes (not to mention that she interviews these experts, sometimes, over pizza) make this book a conversation, more than a treatise. Kolbert talks us through the headiest, most complicated science, breaking down this mass disaster morsel by morsel. This might be The Sixth Extinction’s greatest achievement—it is so smart while also being so quotidian, so urgent while also being so present. And this fits the tone of her argument: our current mass extinction doesn’t feel like an asteroid hitting the planet. It’s amassed by the small ways in which we live our lives. We are crawling, she illuminates, towards the end of the world. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

![Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me]() Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me (2015)

Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me (2015)

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me 1) won the National Book Award for Nonfiction in 2015, 2) was a #1 New York Times bestseller, and 3) was deemed “required reading” by Toni Morrison. What else is there to say? To call it “timely” or “urgent” or even “a prime example of how the personal is, in fact, political” (as I am tempted to do) does not quite capture the unique, grounding, heartbreaking experience of reading this book. Framed as a letter to his teenage son, Between the World and Me is both a biting interrogation of American history and today’s society and an intimate look at the concerns and hopes a father passes down to his son. In just 152 pages, this book touches on the creation of race (“But race is the child of racism, not the father”), the countless acts of violence enacted on black bodies, gun control, and anecdotes from the writer’s own life. Ta-Nehisi Coates, a correspondent for The Atlantic, exercises a journalist’s concision and clarity and fuses it with the flourish of a novelist and the caring instinct of a father. It is a wonderful hybrid. The way the topics, the tones, bleed into one another reads so naturally: “I write you in your fifteenth year. I am writing you because this was the year you saw Eric Garner choked to death for selling cigarettes; because you know now that Renisha McBride was shot for seeking help, and that John Crawford was shot down for browsing in a department store…” The list, of course, goes on. Between the World and Me brilliantly forces us to confront these tragedies again—to remember our own experiences watching the news coverage, to see them in the context of history filtered through Ta-Nehisi Coates’ unsurprised perspective, and to see them anew through the eyes of his disillusioned young son. There is an amazing generosity to these personal glimpses, the moments when the writer turns to his son (says “you”). They catch you off guard. (There are even photographs throughout, like a scrapbook you aren’t sure if you’re allowed to look through.) There have been many books about race, about violence and institutionalized injustice and identity, and there will be more, but none quite so beautifully shattering as this. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

![Andrea Wulf, The Invention of Nature]() Andrea Wulf, The Invention of Nature (2015)

Andrea Wulf, The Invention of Nature (2015)

Andrea Wulf’s 2015 biography of 18th-century German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt—one of the most famous men of his time, for whom literally hundreds of towns, rivers, currents, glaciers, and more are named—is so much more than the story of a single life. Aside from chronicling a remarkably fertile moment in the history of European ideas (Von Humboldt was good buddies with his neighbor in Weimar, Goethe) Wulf reveals in Humboldt a true forebear of present-day ecology, a jack-of-all-trades scientist less concerned with the reduction of the natural world into its constituent specimens than with our place in a broader ecosystem.

And while it doesn’t seem particularly radical now, Humboldt’s proto-environmentalist ideas about the wider world, much of which he mapped and explored, stood in stark contrast to prevailing notions of Christian dominion, that dubious theological position conjured up in aid of empire. Insofar as Humboldt was among the first to understand and articulate the complex systems of a living forest, he was also the first to sound the alarm about the impacts of deforestation (much of which he encountered on his epic journey across the northern reaches of South America). Part adventure yarn, part intellectual history, part ecological meditation, The Invention of Nature restores to prominence an exemplary life, and reminds us of the tectonic force of ideas paired to action. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

![Stacy Schiff, The Witches]() Stacy Schiff, The Witches (2015)

Stacy Schiff, The Witches (2015)

It’s surprising that with a topic as popular and recurring in American culture as the Salem witch trials there have not been more books of this kind. Pulitzer Prize-winning author of the bestselling Cleopatra, Stacy Schiff takes to the Salem witch trials with curiosity and a historian’s magnifying glass, setting out to uncover the mystery that has baffled, awed, and terrified generations since. She pokes at the spectacle that Salem has become in mainstream and artistic depictions—how it has blended with folklore and fiction and has hitherto become a sensationalized event in American history which nonetheless has never been fully understood. Schiff writes that despite the imagination surrounding the Salem witch trials, in reality, there is still a gap in their history of—to be exact—nine months; so the impetus of the book and the intent of Schiff is to penetrate the mass hysteria and panic that ripped through Salem at the time and led to the execution of fourteen women and five men. In her opening chapter, Schiff chillingly sets up the atmosphere of the book and asks key questions that will drive its ensuing narrative: “Who was conspiring against you? Might you be a witch and not know it? Can an innocent person be guilty? Could anyone, wondered a group of men late in the summer, consider themselves safe?” At the heart of Schiff’s historical investigation is the Puritan culture of New England—but part of her masterful synthesis is that she picks apart at each thread of Salem’s culture and evaluates the witch trials from every perspective. Praised for her research as well as her prose and narrative capabilities, Schiff’s The Witches has been described by The Times (London) as “An oppressive, forensic, psychological thriller”; Schiff herself, by the New York Review of Books as having “mastered the entire history of early New England.” A phrase that still haunts me for its resonance throughout human history, is: “Even at the time, it was clear to some that Salem was a story of one thing behind which was a story about something else altogether.” –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

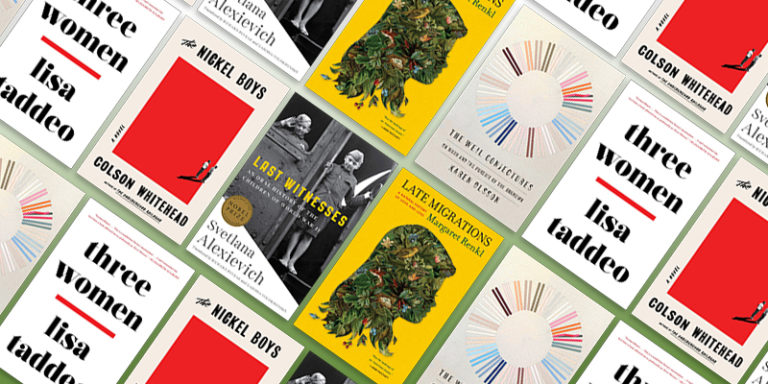

![Svetlana Alexievich, tr. Bela Shayevich, Secondhand Time]() Svetlana Alexievich, tr. Bela Shayevich, Secondhand Time (2016)

Svetlana Alexievich, tr. Bela Shayevich, Secondhand Time (2016)

A landmark work of oral history, Svetlana Alexievich’s Second-hand Time chronicles the decline and fall of Soviet communism and the rise of oligarchic capitalism. Through a multitude of interviews conducted between 1991 and 2012 with ordinary citizens—doctors, soldiers, waitresses, Communist party secretaries, and writers—Alexievich’s account is as important to understanding the Soviet world as Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago. Second-hand Time first appeared in Russia in 2013 and was translated into English in 2016 by Bella Shayevich. As David Remnick wrote in The New Yorker, “There are many worthwhile books on the post-Soviet period and Putin’s ascent…But the nonfiction volume that has done the most to deepen the emotional understanding of Russia during and after the collapse of the Soviet Union of late is Svetlana Alexievich’s oral history…” It is shockingly intimate, Alexievich’s interviewees sharing their darkest traumas and deepest regrets. In their kitchens, at gravesites, each character tells the story of a nation abandoned by the Kremlin. Like much of Alexievich’s work, it is radical in its composition, challenging with its polyphony of distinctive, human voices the “official history” of a society that presented itself as homogeneous and monolithic—an achievement the Nobel committee recognized when it cited the Belorussian journalist for developing “a new kind of literary genre…a history of the soul.” Like her more recent The Unwomanly Face of War and Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II, Alexievich’s project is one of the most important accounts being produced today. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

![Jane Mayer, Dark Money]() Jane Mayer, Dark Money (2016)

Jane Mayer, Dark Money (2016)

In addition to being an incredible work of reporting, Jane Mayer’s Dark Money is a historical document of what happened to America as a small group of plutocrats funded the rise of political candidates who espoused policies and beliefs that had been, until then, considered a part of the fringe right wing of the Republican Party. Mayer describes this group as “a small, rarefied group of hugely wealthy, archconservative families that for decades poured money, often with little public disclosure, into influencing how Americans thought and voted.” Mayer’s painstakingly reported work is a monumental achievement; she lays out, in as much detail as could possibly be available, the mechanisms that allowed this group to channel their wealth and power, with the help of federal law, to a set of institutions that aim to fight scientific advancement, justice-oriented movements, and climate change. In doing so, they have overhauled American politics. As Alan Ehrenhalt put it in a review of the book for The New York Times, she describes “a private political bank capable of bestowing unlimited amounts of money on favored candidates, and doing it with virtually no disclosure of its source.”

The stakes here extend beyond American politics; Mayer points out that Koch money upholds some of the institutions most vigorously fighting climate activism and defending the fossil fuel industry. In 2017, she told the Los Angeles Times, “There are many things you can fix and you can bring back, and there are sort of cycles in American history and the pendulum swings back and forth, but there are things you can damage irreparably, and that’s what I’m worried about right this moment … And that’s why this particular book—because it’s about the money that is stopping this country from doing something useful on climate change.” –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

![David France, How to Survive a Plague]() David France, How to Survive a Plague (2016)

David France, How to Survive a Plague (2016)

To call How to Survive a Plague extensive would be an understatement; France’s account of the epidemic’s earliest days is overwhelmingly generous, letting the reader experience those days, and everything that followed, from within the community that faced it first. France recounts the ways in which scientists and doctors first responded to the virus, tracing the evolution of that understanding from within a small circle to a broad cry for awareness and resources; meanwhile, he shows how a community of people fighting for their lives mobilized alternative systems of communication, education, and support while facing an almost inconceivable wall of barriers to that work. The importance of language in this fight is at the forefront here, from the scientific question of what to call the virus, to its reputation in popular culture as “gay cancer,” to the disagreements within activist groups about how to tell their stories to an unsympathetic world.

This is an enraging history, one of various institutional failures, missed opportunities, hypocrisies, and acts of malice toward a community in crisis, motivated by hatred and horror of queer people and gay men in particular. But I felt equally enraged and in awe. This is a humbling history to read, especially if, like me, you come from a generation of queer people that has been accused of forgetting it. I’m grateful for France’s testimony; it won’t let any of us forget. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

![Andres Resendez, The Other Slavery (2016)]() Andrés Reséndez, The Other Slavery (2016)

Andrés Reséndez, The Other Slavery (2016)

Reséndez’s The Other Slavery is nothing short of an epic recalibration of American history, one that’s long overdue and badly needed in the present moment. The story of the assault on indigenous peoples in the Americas is perhaps well-known, but what’s less known is how many of those people were enslaved by colonizers, how that enslavement led to mass death, and how complicit the American legal system was in bringing that oppression about and sustaining it for years beyond the supposed emancipation in regions in which indigenous peoples were enslaved. This was not an isolated phenomenon. It extended from Caribbean plantations to Western mining interests. It was part and parcel of the European effort to settle the “new world” and was one of the driving motivations behind the earliest expeditions and colonies. Reséndez puts the number of indigenous enslaved between Columbus’s arrival and 1900 at somewhere between 2.5 and 5 million people. The institution took many forms, but reading through the legal obfuscation and drilling down into the archival record and first-hand accounts of the eras, Reséndez shows how slavery permeated the continents. Native tribes were not simply wiped out by disease, war, and brutal segregation. They were also worked—against their will, without pay, in mass numbers—to death. It was a sustained and organized enslavement. The Other Slavery also tells the story of uprising—communities that resisted, individuals who fought. It’s a complex and tragic story that required a skilled historian to bring into the contemporary consciousness. In addition to his skills as a historian and an investigator, Resendez is a skilled storyteller with a truly remarkable subject. This is historical nonfiction at its most important and most necessary. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

![Rebecca Traister, All the Single Ladies]() Rebecca Traister, All the Single Ladies (2016)

Rebecca Traister, All the Single Ladies (2016)

One night, facing a brief gap between plans with different people, I took Rebecca Traister’s All the Single Ladies to a bar. A few minutes after I ordered, deep in Traister’s incredible, extensive history of single women in America, a server came over to offer me another, more isolated seat at the end of the bar, “so you don’t feel embarrassed about being alone,” she said, quietly. I assured her I was okay, trying not to laugh. She was just so worried.

I turned back to my book to find Traister describing this kind of cultural distress—a woman, alone, in public?!—at a new generation of unmarried adult women, who are more autonomous and numerous today than ever before. Far from marking a crisis in the social order, Traister writes, this shift “was in fact a new order … women’s paths were increasingly marked with options, off-ramps, variations on what had historically been a very constrained theme.” She examines the history of unmarried women as a social and political force, including the activists who devoted their lives to establishing a greater range of educational, familial, and economic choices for women, with particular attention to the ways in which that history is also one of racial and economic justice in the US. Traister also highlights the networks of social support that women have created in order to survive patriarchy and establish lifestyles that did not depend on it; intimacy and communication among unmarried women, she shows, were the backbone of activist and reform movements that successfully challenged the dominant order.

The book draws on interviews from dozens of women of varying backgrounds, and their firsthand accounts are a portrait of life amid a historic shift toward female autonomy. Their stories, and Traister’s analysis, make it clear that even as options for many women are expanding, those options are not equally available or beneficial to all women. This is a stunning reckoning with the state of women’s independence and the policies that still seek to curtail it. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

![Caroline Fraser, Prairie Fires]() Caroline Fraser, Prairie Fires (2017)

Caroline Fraser, Prairie Fires (2017)

Prairie Fires, Caroline Fraser’s Pulitzer Prize- and National Book Critics Circle Award-winning biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder is not just a painstakingly researched and lyrically realized account of how the Little House on the Prairie author decanted the poverty and precarity of her homesteader family’s existence into narratives of self-reliance and perseverance—although it is that—it is also a meditation on the human need “to transform the raw materials of the past into art.” Full disclosure, I did not read the Little House on the Prairie books as a child and have no sentimental attachment to Laura, Pa or Ma. But in looking at the life behind the books, Wilder emerges as a tenacious, sometimes fragile figure, and as a literary operator of uncommon nous and self-awareness. Drawing on unpublished manuscripts, letters, diaries, and land and financial records, Prairie Fires has all the essentials of a great history book. Most importantly, Fraser’s great skill is in pulling back the veils of mythology that have enshrouded her subject and the era her works helped to define, enabling us to see both the real people and the myths themselves with fresh, critical eyes. There is no romanticizing of the Frontier, and a very real understanding of the sentimentality and bias of an overtly racist understanding of “westward expansion.” It is a remarkable book. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

![David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass]() David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (2018)

David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (2018)

In 2017, monuments commemorating heroes of the Confederacy were being debated, defaced and toppled throughout the United States. That same year, months before President Trump signed a law creating a commission to plan for the bicentennial of Frederick Douglass’ birth, he infamously seemed to suggest that Douglass was still around, doing an “amazing job” and “getting recognized more and more.” The irony was hard to miss: it was easy to eulogize a past that was not comprehensively, nor even fundamentally understood. One achievement of historian David Blight’s monumental study of the former slave turned abolitionist is the thoroughness with which it examines the man’s development across three autobiographies he produced in the span of ten years. The popular image of Douglass has long been that of a bushy-haired man affixed to Abraham Lincoln’s side, delivering rousing speeches on abolition and the sins of slavery. And while there is basic truth to that, Blight sets out to fill the gaps in public understanding, guiding readers from the Maryland slave plantation where Douglass was born to the many stops along his European speech circuit, when he established himself as one of the world’s most recognizable opponents of slavery. The vague circumstances of Douglass’ birth (he was born to an enslaved woman and a white man who may also have been his owner) later compelled him to create his own life narratives, a task that he accomplished both in writing and oratory. Blight’s engagement with Douglass’ writing also marks the biography as a triumph of public-facing textual criticism. For decades before Prophet of Freedom astonished critics and general readers, Blight had been making his name as one of the leading Douglass scholars in the US. Blight’s work was not historical revisionism, but rather a considered analysis of a man who relied on actions as much as words. Many may be surprised to learn, for example, what a vocal supporter Douglass was of the Civil War and violence as a necessary means to dismantle the system that had nearly destroyed him. Prophet of Freedom feels as definitive as a Robert Fagles translation of Homer—we hope it’s not the final word, though it will take quite the successor to produce a worthwhile follow-up. –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

![Robert Macfarlane, Underland]() Robert Macfarlane, Underland (2019)

Robert Macfarlane, Underland (2019)

One hesitates to label any book by a living writer his “magnum opus” but Macfarlane’s Underland—a deeply ambitious work that somehow exceeds the boundaries it sets for itself—reads as offertory and elegy both, finding wonder in the world even as we mourn its destruction by our own hand. If you’re unfamiliar with its project, as the name would suggest, Underland is an exploration of the world beneath our feet, from the legendary catacombs of Paris to the ancient caveways of Somerset, from the hyperborean coasts of far Norway to the mephitic karst of the Slovenian-Italian borderlands.

Macfarlane has always been a generous guide in his wanderings, the glint of his erudition softened as if through the welcoming haze of a fireside yarn down the pub. Even as he considers all we have wrought upon the earth, squeezing himself into the darker chambers of human creation—our mass graves, our toxic tombs—Macfarlane never succumbs to pessimism, finding instead in the contemplation of deep time a path to humility. This is an epochal work, as deep and resonant as its subject matter, and would represent for any writer the achievement of a lifetime. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

![Patrick Radden Keefe, Say Nothing]() Patrick Radden Keefe, Say Nothing: A True History of Memory and Murder in Northern Ireland (2019)

Patrick Radden Keefe, Say Nothing: A True History of Memory and Murder in Northern Ireland (2019)

Attempting, in a single volume, to cover the scale and complexity of the Northern Ireland Troubles—a bloody and protracted political and ethno-nationalist conflict that came to dominate Anglo-Irish relations for over three decades—while also conveying a sense of the tortured humanity and mercurial motivations of some of its most influential and emblematic individual players and investigating one of the most notorious unsolved atrocities of the period, is, well, a herculean task that most writers would never consider attempting. Thankfully, investigative journalist Patrick Radden Keefe (whose 2015 New Yorker article on Gerry Adams, “Where the Bodies Are Buried”, is a searing precursor to Say Nothing) is not most writers. His mesmerizing account, both panoramically sweeping and achingly intimate, uses the disappearance and murder of widowed mother of ten Jean McConville in Belfast in 1972 as a fulcrum, around which the labyrinthine wider narrative of the Troubles can turn. The book, while meticulously researched and reported (Radden Keefe interviewed over one hundred different sources, painstakingly sorting through conflicting and corroborating accounts), also employs a novelistic structure and flair that in less skilled hands could feel exploitative, but here serves only to deepen our understanding of both the historical events and the complex personalities of ultimately tragic figures like Dolours Price, Brendan Hughes, and McConville herself—players in an attritional drama who have all too often been reduced to the status of monster or martyr. Once you’ve caught your breath, what you’ll be left with by the close of this revelatory hybrid work is a deep and abiding feeling of sorrow, which is exactly as it should be. –Dan Sheehan, BookMarks Editor

***

Dissenting Opinions

The following books were just barely nudged out of the top ten, but we (or at least one of us) couldn’t let them pass without comment.

![Maggie Nelson, The Art of Cruelty]() Maggie Nelson, The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning (2011)

Maggie Nelson, The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning (2011)

Maggie Nelson, if evaluated from a first glance at her authored works, may appear to be a paradox. That the author of Bluets, a moving lyric essay exploring personal suffering through the color blue, also wrote The Red Parts, an autobiographical account of the trial of her aunt’s murderer, may seem surprising. Not that any person cannot and does not contain multitudes but the two aesthetics may seem diametrically opposed until one looks at The Art of Cruelty and understands Nelson’s fascination with art on the one hand, and violence on the other. Nelson hashes out the intersection of the two across multiple essays. “One of this book’s charges,” she writes, “is to figure out how one might differentiate between works of art whose employment of cruelty seems to me worthwhile (for lack of a better word), and those that strike me as redundant, in bad faith, or simply despicable.” The Art of Cruelty is a self-proclaimed diagram of recent art and culture and does not promise to take sides, to deliver ethical or aesthetic claims masquerading as some declarative truth on the matter. So cruelty is very much approached from Nelson’s poetic sensibility, with a degree of nuance, and an attitude of reflection and curiosity but also one of a certain distance so that all the emotions—anger, disgust, discomfort, thrill etc.—can be viewed as part of a whole rather than in isolation. Cruelty, counterbalanced with compassion—especially with reference to Buddhism—is certainly not hailed by Nelson as a cause for celebration but worthy of rumination and analysis so that it is not employed tacitly and without recourse. No book could ever, I think, provide an exhaustive evaluation of this topic, nor is Nelson’s approach that of a philosopher or art-historian looking to propose a theory. Nevertheless, she dexterously, and creatively, manages to hold a mirror to our culture’s fascination with cruelty and invites us to reflect on our personal reasons for indulging it. –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

![the beast martinez]() Óscar Martinez, The Beast (2013)

Óscar Martinez, The Beast (2013)

For over a decade, Martinez has been a witness and a chronicler of the ground-level effects of the war on drugs, reporting from across Latin America with a special focus on Central America and his home country of El Salvador, where more recently he’s been writing about the bloody culture of MS-13 and other narco-cliques that have expanded their power. Before that, he was charting the plight of migrants running the terrible gauntlet across borders and through narco-controlled territories. Martinez rode the dreaded train known as “The Beast” and collected the stories of those traveling north on this perilous journey. While crime isn’t strictly the focus of the book, Martinez looks at the direct effects of mass crime at a regional/global level, as well as the outlaw communities springing up to prey on the vulnerable. The subject matter is dark, but Martinez writes with the terrible, piercing clarity of a Cormac McCarthy. The Beast is a dispatch from a nearly lawless land, where families struggle and suffer, narcos get richer, violence spreads, the drugs head north, the guns head south, and so it goes on. Forget the rhetoric, the politics, and the propaganda. The Beast is the real story of the drug war. “Where can you steer clear of bandits?” Martinez asks. “Where do the drugs go over? Where can you avoid getting kidnapped by the narcos? Where is there a spot left with no wall, no robbers, and no narcos? Nobody has been able to answer this last question.” To call this book prescient disregards how long our problems have persisted, and how long we’ve managed to ignore the chaos our country’s policies have created. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

![Matthew Desmond, Evicted]() Matthew Desmond, Evicted (2016)

Matthew Desmond, Evicted (2016)

There are more evictions happening now, per capita, in the United States, than there were during the Great Depression. As it turns out, there’s a lot of money to be made from poverty—not, course, for those who need it, but for the landlords who orchestrate the kind of housing turnover that traps people in deeper and longer cycles of debt. Poverty in America has long been conflated with moral failure, but as Matthew Desmond’s Evicted illustrates in great detail, if there’s any moral failing happening, it’s with those who would take advantage of such systemic and generational iniquities.

Desmond, a Princeton-trained sociologist and MacArthur fellow, went to see for himself in 2008, at the height (depths?) of the housing crisis, undertaking a year-long study of eight Milwaukee-area families, spending six months in a mobile home and another six months in a rooming house, creating much more than a journalist’s snapshot of life as an American renter. With Evicted, Desmond has widened our perspective on cyclical hardship and its disproportionate impact on people of color, illustrating (with neither the leering nor the condescension of so much reporting on the poor) that eviction is more often a cause of poverty than a symptom. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

![Yuri Slezkine, The House of Government]() Yuri Slezkine, The House of Government (2017)

Yuri Slezkine, The House of Government (2017)

I recommend this book to those who wish to demonstrate their physical strength in public and show off that they can read a giant Russian history book one-handed, but also I recommend this book to everyone, ever, in the world, because it’s so fantastic. At first glance, this is a lengthy tome inspired by a Tolstoyan approach to lyrical history, ostensibly concerned with the history of an apartment complex that was home to much of the early Soviet elite—and was subsequently depopulated by Stalinist purges. Within this apartment building, however, lay the central irony of the revolution—those who believed deeply enough in an idealistic system to embrace violent, repressive means of revolution, were soon enough subjected to those same mechanisms of repression. From this central irony, Slezkine, always concerned with how the micro fits into the macro, zooms out to look at the Soviets as just another bunch of millenarians (and to understand what an insult that is, you’ll have to pick up the book). –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

![Richard Lloyd Parry, Ghosts of the Tsunami]() Richard Lloyd Parry, Ghosts of the Tsunami (2017)

Richard Lloyd Parry, Ghosts of the Tsunami (2017)

Richard Lloyd Parry, Tokyo bureau chief for The Times of London, begins his book by describing the way his office building in Tokyo shook in March 2011 when an earthquake hit the city. He called his family and checked that they were OK and then walked through the streets to see the damage. Used to quakes, this one seemed bad, but not the worst he had lived through. Less than an hour after the earthquake, though, a tsunami killed an estimated 18,500 Japanese men, women and children. In Ghosts, Parry focuses his story on Okawa, a tiny costal village where an entire school and 74 children washed away. In somewhat fragmentary threads, Parry explores the families that survived, the ghosts that follow them, and the landscape of a place that will never be the same. In localizing the story in one community, Parry is able to clearly define the painfully individual fallout of a national tragedy. It is emotionally draining to read, which is a warning I give everyone when I recommend the book (which I do constantly). But it is one of my favorite books and I would be remiss not to include in our list for best nonfiction of the decade. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

![Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing]() Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing (2019)

Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing (2019)

I grew up in a town named after a body of water—Rye Brook—and went to a high school also named after that body of water—Blind Brook—but growing up, no one seemed to actually know where the brook was, at least none of the kids. We didn’t talk about it, except to note its hiddenness—it’s behind the school, someone once told me, while another person said it was behind that hotel, behind the park, behind the airport. Recently, I decided to find it on a map and noticed, for the first time, that the brook, far from being a hidden thing, defines the majority of Rye Brook’s borders. Recognizing this foundational feature of my hometown for the first time, more than a decade after I left it, was disorienting, completely re-rendering my perception of the place I thought I knew best.

My search that day came after I read Jenny Odell’s account of her similar awakening to the ecology of her hometown, Cupertino, and all the features in or around it: Calabazas Creek, nearby mountains, and the San Francisco Bay. “How could I have not noticed the shape of the place I lived?” she writes, and, later, describing her own disorientation in a way that resonates with my own, added, “Nothing is so simultaneously familiar and alien as that which has been present all along.”

One way of describing the premise of this book is to say “that which has been present all along” is reality itself: each of us, from day to day, living our physical lives in a physical place. But in 2019, life doesn’t usually feel like that; it feels like an onslaught of forces that aim to turn our attention away from this reality and monetize it in a shapeless virtual space. In that environment, Odell writes, doing “nothing,” or finding any way to disrupt the capitalistic drive to monetize, is an act of political resistance, even as she recognizes that not everyone has the economic security or social capital to opt out. “Just because this right is denied to many people doesn’t make it any less of a right or any less important,” she writes. This book also draws on philosophy, utopian movements, and labor organizing to describe how various people have attempted to “do nothing” in their own way throughout history, with an outlook that is grounded in ecology. (And bird watching!) Ultimately, Odell writes, the act of doing nothing creates space for the kind of contemplation and reflection that is essential to activism and to sustaining life. I experienced this book as a space of sanity and as a beginning; I hope you do, too. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

***

Honorable Mentions

A selection of other books that we seriously considered for both lists—just to be extra about it (and because decisions are hard).

Peter Hessler, Country Driving (2010) · Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (2010) · Barbara Demick, Nothing to Envy (2010) · Marina Warner, Stranger Magic (2012) · Jon Meacham, Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power (2012) · Oscar Martinez, The Beast (2013) · Katherine Boo, Behind the Beautiful Forevers (2013) · Mary Ruefle, Madness, Rack, and Honey (2013) · David Epstein, The Sports Gene (2013) · Sheri Fink, Five Days at Memorial (2013) · David Finkel, Thank You for Your Service (2013) · George Packer, The Unwinding (2013) · Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything (2013) · Roxanne Dunbar-Oritz, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States (2014) · Sarah Ruhl, 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write (2014) · Olivia Laing, The Trip to Echo Spring (2014) · Hermione Lee, Penelope Fitzgerald (2014) · Mary Beard, SPQR (2015) · Sam Quinones, Dreamland (2015) · Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped From the Beginning (2016) · Ruth Franklin, Shirley Jackson (2016) · Arlie Russell Hochschild, Strangers In Their Own Land (2016) · Margot Lee Shetterly, Hidden Figures (2016) · Laura Dassow Walls, Henry David Thoreau: A Life (2017) · David Grann, Killers of the Flower Moon (2017) · Elizabeth McGuire, Red at Heart (2017) · Frances FitzGerald, The Evangelicals (2017) · Jeff Guinn, The Road to Jonestown (2017) · Michael Tisserand, Krazy (2017) · Lawrence Jackson, Chester Himes (2017) · Zora Neale Hurston, Barracoon (2018) · Beth Macy, Dopesick (2018) · Shane Bauer, American Prison (2018) · Eliza Griswold, Amity and Prosperity (2018) · David Quammen, The Tangled Tree (2018).

Castor and Pollux, the Heavenly Twins, Giovanni Battista Cipriani

Castor and Pollux, the Heavenly Twins, Giovanni Battista Cipriani

Svetlana Alexievich trans. by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky,

Svetlana Alexievich trans. by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky,  Colson Whitehead,

Colson Whitehead,  Lisa Taddeo,

Lisa Taddeo,  Sarah Rose Etter,

Sarah Rose Etter,  Adrian McKinty,

Adrian McKinty,  Karen Olsson,

Karen Olsson,  Claudia D. Hernández,

Claudia D. Hernández,  Madeline ffitch,

Madeline ffitch,  Margaret Renkl,

Margaret Renkl,  Chelsea Johnson, LaToya Council, and Carolyn Choi, illustrated by Ashley Seil Smith,

Chelsea Johnson, LaToya Council, and Carolyn Choi, illustrated by Ashley Seil Smith,

Michelle Alexander,

Michelle Alexander,  Siddhartha Mukherjee,

Siddhartha Mukherjee,  Rebecca Skloot,

Rebecca Skloot,  Timothy Snyder,

Timothy Snyder,  Isabel Wilkerson,

Isabel Wilkerson,  Robert A. Caro,

Robert A. Caro,  Tom Reiss,

Tom Reiss,  Elizabeth Kolbert,

Elizabeth Kolbert,  Ta-Nehisi Coates,

Ta-Nehisi Coates,  Andrea Wulf,

Andrea Wulf,  Stacy Schiff,

Stacy Schiff,  Svetlana Alexievich, tr. Bela Shayevich,

Svetlana Alexievich, tr. Bela Shayevich,  Jane Mayer,

Jane Mayer, David France,

David France,  Andrés Reséndez,

Andrés Reséndez,  Rebecca Traister,

Rebecca Traister,  Caroline Fraser,

Caroline Fraser,  David W. Blight,

David W. Blight,  Robert Macfarlane,

Robert Macfarlane,  Patrick Radden Keefe,

Patrick Radden Keefe,  Maggie Nelson,

Maggie Nelson,  Óscar Martinez,

Óscar Martinez,  Matthew Desmond,

Matthew Desmond,  Yuri Slezkine,

Yuri Slezkine,  Richard Lloyd Parry,

Richard Lloyd Parry, Jenny Odell,

Jenny Odell,

Professor Costlow on the last day of classes before Bates College closed down because of the coronavirus pandemic. Photo: Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College.

Professor Costlow on the last day of classes before Bates College closed down because of the coronavirus pandemic. Photo: Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College.