![]()

This year’s fiction and nonfiction longlists for the Brooklyn Library Literary Prize honor “books which—by subverting literary forms, pushing against established ways of thinking, or otherwise introducing new or challenging ideas—speak to the Library’s ideals. This will connect the prize to the Library’s mission to create a welcoming environment in which all members of the borough’s diverse community—one of the most socially and culturally complex in the country—can come together to contemplate urgent social, political and artistic questions.” The fiction list includes Lesley Nneka Arimah‘s What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky, Mohsin Hamid‘s Exit West, Michelle Tea’s Black Wave, and Lidia Yuknavitch‘s The Book of Joan. Nonfiction candidates include David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon, Pankaj Mishra‘s Age of Anger, Phoebe Robinson‘s You Can’t Touch My Hair and Sarah Schulman‘s Conflict Is Not Abuse.

A new translation of Nobel Prize winner Svetlana Alexievich‘s first book is “a frightening and lacerating book — as beautiful as a ruined cathedral,” Joshua Cohen‘s new novel is a “Jewish Sopranos,” Tamara Shopsin‘s memoir “serves up the old, weird Greenwich Village,” Zizi Clemmons‘s first novel is dubbed “the debut novel of the year,” and Achy Obejas‘s new collection proves her to be “one of the most important Cuban writers of our time.”

![The Unwomanly Face of War]()

Svetlana Alexievich, The Unwomanly Face of War

Alexievich won the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature “for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time.” In her first book, newly translated into English by Larissa Volokhonsky and Richard Pevear, she develops her collage-style oral history in interviews with some of the 1 million women who fought in the Red Army during World War II.

Alexievich “writes movingly about the 1 million women who served in the Red Army as snipers, medics, foot soldiers, pilots, tank drivers, mechanics and other vital jobs,” writes Elaine Margolin (Truthdig). “She explores difficult terrain. What is it like to kill someone? What were they most afraid of? How have they dealt with their traumas? What effect has their war experiences had on their children and grandchildren? She observes that women remember war differently. They do not focus on heroics or the intricacies of battle as men do. Little moments remain etched in their memory and change them forever. This is what interests Alexievich, who calls herself a ‘historian of the soul.’”

“The catalogue of horrors and deprivations of this book is so vivid it seems monstrous not to fathom that time puts its most awful pressures on the story of a trauma,” writes John Freeman (Boston Globe). “It carves them into the most true instrument. Alexievich says as much in her introduction. To be so hungry as to eat potato peelings; to watch your children mimic the most deformed and yet courageous bravery. ‘[M]y mama can’t leave,’ a mother recalls her young daughter telling a pilot who wants the two of them to board his plane and escape. ‘She has to fight the fascists.’ Thousands upon thousands of them came home, and in this frightening and lacerating book—as beautiful as a ruined cathedral—Alexievich has turned their voices into history’s psalm.”

Kate Tuttle (Newsday) concludes:

At a time when Americans and Russians once again find ourselves in a strange relationship—not a Cold War, but not the allies we were during World War II—there’s something powerful about such close access to these women’s feelings. The deceptively simple form Alexievich deploys allows for an emotional range from utter despair to a kind of transcendent hope. “Do you know how beautiful a morning at war can be? Before combat,” one army surgeon says, “you look and you know: this may be your last. The earth is so beautiful.”

![]()

Joshua Cohen, Moving Kings

This Year Cohen was named one of Granta’s Best Young American Writers. His new novel showcases his audacious talent. The starred Kirkus Review: “Cohen shows an impressive knowledge of life in the cab of a moving van and in the ranks of the Israeli Defense Forces. He touches on two wars and two combat zones (counting brief allusions to Afghanistan). He is funny and caustic and has a marvelous snap in his dialogue.”

“Moving Kings is a brilliant book whose brilliance comes via a bait and switch,” writes Mark Athitakis (Los Angeles Times). “It opens as a comic portrait of a midlife crisis, but concludes as a somber cautionary tale frothing with cataclysms, including fire and gunplay. It starts tucked deep into a subculture—in this case the peculiarities of running a New York City-area moving company—but expands to consume whole swaths of race and religion. It comes on as unassuming yet stylish, but circles around tricky questions of occupation and power in the U.S. and Israel. And yet none of it feels messy or overreaching—indeed, it feels master-planned to slowly unsettle your convictions, as the best novels do.”

Ron Charles (Washington Post) notes, “The clash of expectations between a rough American businessman and an Israeli innocent abroad provides the basis for some smart comedy, and Cohen is particular adept with moments of silly absurdity. He also exercises a fantastically agile style that pushes hard against the banisters of traditional grammar. The novel’s voice freely veers into these characters’ minds, picking up their thoughts and accents, mixing with the narrator’s own straight-faced asides. But for all its domestic humor, there’s barbed wire running through this story, stretching tight from New York to the West Bank. The moving business, after all, is not just a matter of transporting happy families to bigger homes. Much of David’s profit is squeezed from evictions: emptying people’s apartments as their lives careen toward ruin.”

James Wood (The New Yorker) calls Moving Kings “a Jewish Sopranos” and concludes:

Moving Kings is a strange, superbly unsuccessful novel. There’s not a page without some vital charge—a flash of metaphor, an idiomatic originality, a bastard neologism born of nothing. You could say that it is patchworked with successes: David King in the Hamptons, Yoav and Uri in the Israeli Army, the King’s Moving crew at work in New York, Avery Luter flailing in his mother’s house. Yet these stories are more convincing than the connections, thematic and formal, offered to bind them. Cohen never finds that deep novelistic form, that tensile coherence, which Woolf idealized. This is a book of brilliant sentences, brilliant paragraphs, brilliant chapters. Here things flare singly, a succession of lighted matches, and do not cast a more general illumination. But Cohen opened his previous novel with a challenge: “There’s nothing worse than description: hotel room prose. No, characterization is worse. No, dialogue is.” So if his most accessible novel yet, rich in all three despised elements, frustrates conventional satisfactions, is it because he has failed to find the right form or because he is trying to found a new one?

![]()

Tamara Shopsin, Arbitrary Stupid Goal

Shopsin offers an insider’s look at a Greenwich Village institution called The Store, her family’s grocery/café at Morton and Bedford Streets. Critical response is rapturous.

Arbitrary Stupid Goal “is a little like a meal at Shopsin’s, her family’s restaurant,” writes Alexandra Schwarz (The New Yorker). “It’s got a bit of everything, in a way that shouldn’t rightly work but does. Antique gumball machines; crossword puzzles; scam artists; perverted supers; foul apartments; fouler mouths; curry mixed into peanut butter; chewing gum stuck in armpits; known celebrities, like John Belushi and Joseph Brodsky, and unknown ones, like Willoughby, a basement-dwelling genius and the de-facto mayor of Morton Street—it’s all thrown into the pot, seasoned salty-sweet with a proprietary blend of so-it-goes nostalgia, and out it comes, delicious.”

Heller McAlpin (NPR) finds Shopsin’s book “neither arbitrary or stupid.”

Arbitrary Stupid Goal is an ode to unconventionality and an elegy to Greenwich Village in the 1970s and 80s, which was crime-riddled but also “a very tolerant place.” Shopsin reminds us that the Village used to attract “fringe people,” whom she was brought up to believe were “the nutrients of New York City.” After describing a period when what the family still calls “The Store” was robbed regularly—including twice in one day—she comments, “It is easy to cite the bad in the filthy chaos of New York before luxury condos. It is harder to express the spirit, life, and community that the chaos and inefficiency bred.” That “spirit, life, and community” are exactly what Shopsin conveys in this rich smorgasbord of memories . . .

“Shopsin’s story revolves around her father, whose declining health and mental acuity are heartbreakingly depicted—and Willy, her father’s best friend and mentor, whom she cared for at the end of his life, as Mercer Street changed forever,” writes Cory Doctorow (Boing Boing). “These two larger-than-life characters are the avatars for a different, pre-financialized New York, a lost world where family and art and laughter and craft were more important than mere money, when weirdos could flourish in the cracks and make cities into vibrant and surprising places. Their stories—dirty, funny, criminal, delicious—are a reminder of something we’ve lost in living memory: a moment before the orderliness of long supply chains and complex financial derivatives squeezed the handmade and odd out of the world. They’re the tea-leaves that brewed Make: magazine and the maker movement, avatars of indie-rock and indie culture.”

![]()

Zinzi Clemmons, What We Lose

Clemmons grew up in Philadelphia and studied with Paul Beatty in the MFA program at Columbia. The starred Kirkus Review calls her first novel “A compelling exploration of race, migration, and womanhood in contemporary America.”

“In just a slim 200 pages, Clemmons traverses the rocky terrain of race in both America and South Africa,” writes Kirkus Review’s Stephanie Buschardt. “Thandi, like Clemmons, is mixed-race. Her mother is South African, from Johannesburg, a city still reeling from its violent past, and her father was born in New York but relocated to Philadelphia, where they safely reside nestled in a wealthy, mostly white suburb. For Thandi’s parents—who pride themselves on their education—this is a monumental achievement, whereas Thandi feels like an outsider in a community in which, because of her heritage and light complexion, she’s adrift. ‘American blacks were my precarious homeland—because of my light skin and foreign roots, I was never fully accepted by any race. Plus my family had money, and all the black kids in my town came from the poorer areas,’ Clemmons writes. ‘I was a strange in-betweener.’”

Megan O’Grady (Vogue) calls What We Lose “the debut novel of the year.” “Boldly innovative and frankly sexual, the collage-like novel mixes hand-drawn charts, archival photographs, rap lyrics, sharp disquisitions on the Mandelas and Oscar Pistorius, and singular meditations on racism’s brutal intimacies. ‘I’ve often thought that being a light-skinned black woman is like being a well-dressed person who is also homeless,’ reflects Thandi, recalling her mother’s warnings that darker girls will be jealous of her.”

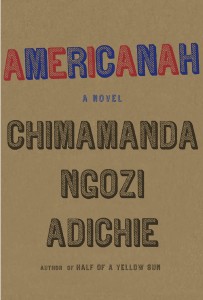

“In its preoccupation with maternal loss, What We Lose recalls Jamaica Kincaid’s wonderful The Autobiography of My Mother, though the latter concerns a much earlier and life-defining loss,” writes Sarah Gilmartin (Irish Times). “Brit Bennett’s recent debut The Mothers also comes to mind. Clemmons and Bennett both offer intelligent perspectives on issues affecting black women in modern America. With its contemplations on race and its collage of genres, there are parallels with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, though What We Lose is in micro form by comparison.This is not to disparage what Clemmons has achieved in her affecting novel. Although disjointed, it is a book brimming with ideas.”

![]()

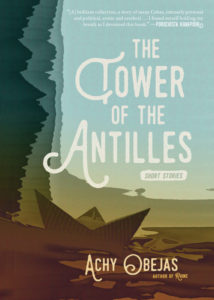

Achy Obejas, The Tower of the Antilles

In her new collection, Obejas, a Cuban-American poet, short story writer, novelist, journalist and translator, traces the complex borders between island homeland and reinvention in the U.S. Booklist’s Donna Seaman writes: “For all the human tumult and deftly sketched and reverberating historical and cultural contexts that Obejas incisively creates in these poignant, alarming tales, she also offers lyrical musings on the mysteries of the sea and the vulnerability of islands and the body. Obejas’ plots are ambushing, her characters startling, her metaphors fresh, her humor caustic, and her compassion potent in these intricate and haunting stories of displacement, loss, stoicism, and realization.”

Porochista Khakpour (Electric Literature) selects the story “Kimberle” from this new collection for Recommended Reading, and calls it Obejas’s “masterpiece.”

Sexuality, nationality, gender, ethnicity and race all come together here in those everyday ways that they do in our lives, and then some. The then some is the way this is love story and thriller and horror and folktale and parable all at once, not in some foggy watercolor liminality but in the most stark sunlight and lighting and blood and bruise you can imagine. Obejas is the sort of writer whose gifts are so far beyond mine that the more I study her — I’ve been her reader for more than two decades, now — the more confused I am at how she builds it all. I don’t even get to ask my how does she do it? that the writer in me usually can’t let go of when I read. I lose myself too quickly in her dreams.

Ashley Miller (Atticus Review) writes, “Each story rolls open as a wave and then recedes, ending as abruptly as a wave crashing against the shore, just as another story-wave rushes forward and unfolds. In many instances, like the ex-Cubans of the stories reaching for possibilities, for promise of more, we turn the page, but the next story begins before our mind is ready to let go. In a way, this forces the reader to submerge, to swallow the whole of The Tower of the Antilles in a single gulp, to face the sadness of being adrift and holding our breath as the current takes us under, hoping to break surface and breathe again.”

Christopher R. Alonso (Miami Rail) concludes:

These stories are filled with yearning for an unattainable place, something characters desire yet can never quite grasp—whether they’ve left the island or not. These tales are both nostalgic and entirely new. Obejas sneaks under the skin, revealing emotions tied up at the dock, cuts the rope, and sets them free. The Tower of the Antilles proves, once again, why Achy Obejas is one of the most important Cuban writers of our time.

25. The VIDA Count Expands, Shows Slight Improvement

25. The VIDA Count Expands, Shows Slight Improvement 24. A Nonfiction, Female Writer Wins the Nobel Prize

24. A Nonfiction, Female Writer Wins the Nobel Prize 23. Paris Finds Solace in Hemingway

23. Paris Finds Solace in Hemingway 22. White Guys Deprived of Awards

22. White Guys Deprived of Awards 21. The Rise of Literary Conspiracy Theories

21. The Rise of Literary Conspiracy Theories 20. Authors Officially Named “Influential”

20. Authors Officially Named “Influential” 19. The New Republic Becomes Even Newer

19. The New Republic Becomes Even Newer 18. Joan Didion Models, Inspires Internet Fights

18. Joan Didion Models, Inspires Internet Fights 17. DFW Finally Gets the Movie He Never Wanted

17. DFW Finally Gets the Movie He Never Wanted 16. The US Government Surprises No One

16. The US Government Surprises No One